Sentence Vacated, Adnan Syed Released

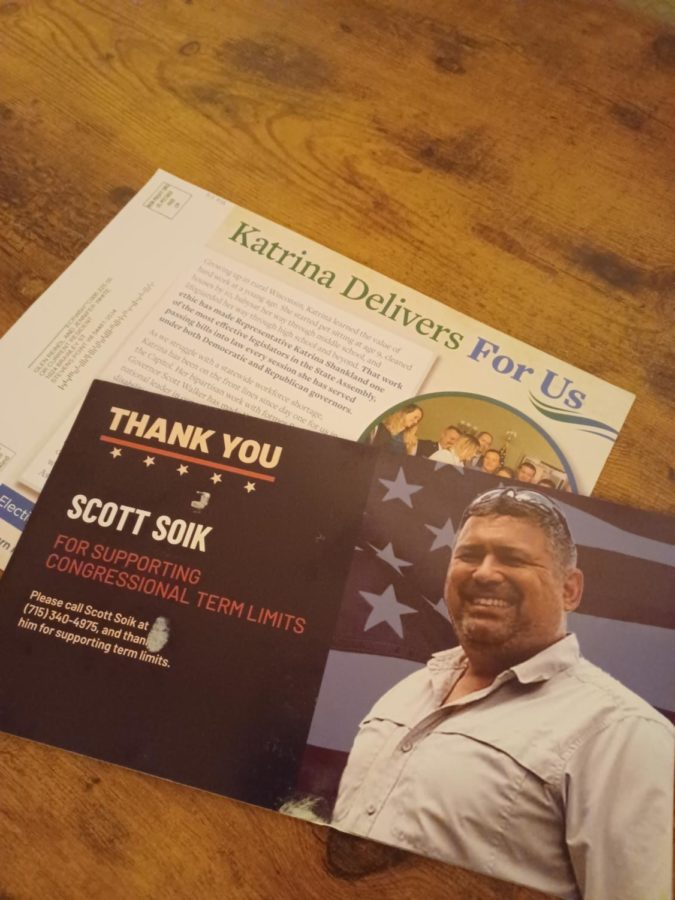

Adnan Syed celebrates as he leaves the courthouse.

October 20, 2022

An untrustworthy alibi, an inapt lawyer, and a series of flawed pieces of evidence. For those who have listened to ‘Serial’, a podcast written and narrated by investigative director Sarah Koenig, the murder of Hae Min Lee may sound familiar. The same goes for those who have listened to the ‘Undisclosed’ podcast or watched HBO’s The Case Against Adnan Syed. But for those who have not even heard of either, here’s what happened: in January of 1999, a teenage girl went missing. She was supposed to pick up her younger cousin but ultimately failed to do so. This was out of character for her because she was both punctual and responsible, and she picked up her cousin almost every day. The teenage girl was Hae Min Lee, a popular senior who attended Woodlawn high school, in Baltimore, Maryland. Lee had recently moved on from her ex-boyfriend, a fellow senior at Woodlawn, Adnan Syed. She now dated her coworker from Lenscrafters.

Just four weeks later, in February, Lee’s remains were found in a shallow grave. The police report says that she was “partially buried […] approximately 127 feet off the roadside”, but still within Leakin Park. Detectives ultimately ruled the death as a homicide, saying that someone had intentionally strangled Lee. And that someone, according to the public, was Adnan Syed.

Syed’s conviction has recently been vacated thanks to a series of newfound Brady violations

Brady violations, according to Syed’s attorney, are “absolutely crucial” for the prosecutors to hand over. “Brady material”, in the words of Cornell Law School, consists of “evidence the prosecutor is required to disclose”. A violation of this rule is a direct result of the prosecution not sharing evidence that could change the outcome of a trial, which is just what occurred in Adnan’s case.

But that’s not all…

Jay Wilds, the key alibi in Syed’s conviction, had told police that he knew of Syed’s plan to kill Lee, as Syed had told Wilds of his plan “multiple times”. But when Wilds was asked about why he didn’t directly go to the police with this information, he claimed that he was afraid, because Syed had said that if he ever did so, he would rat out Wilds for his illegal marijuana sales. On top of that, Wilds had changed his testimony not once, but three different times. (And then again, just a few years ago!) The only consistency that can be found in Wilds’s story was that Syed had shown him Lee’s cadaver before ‘forcing’ him to help bury her—but even then, Wilds’s classmates say that he was also known to lie and brag, especially when it came to things that didn’t happen to him.

That, on top of DNA evidence that was retested in 2016, which found no matches (including Syed’s), as well as some evidence that the original trial’s phone records were flawed, could potentially change everything.

For the Lees, this entire thing is an inescapable nightmare

The Brady violations were not only news to the nation, but also Lee’s own family. Their attorney spoke out a few days ago, admitting that they had never really gotten any sort of warning about Syed’s release. “My clients,” he said, “want the truth to come out. If the truth is that someone killed their sister, or daughter, they want to know that more than anybody”, which is true, but it’s also something that people—especially true crime addicts—often forget. They are so caught up in their heads, and their emotions; feeling bad for Syed and being mad at the justice system, that they nearly forget who the real victim is, and how much she, alongside her family, have already suffered. They desensitize the real issue—a teenage girl was murdered—and focus on the details. People don’t realize that the Lees have been suffering for more than 20 years, and just when they think they’ve found justice, it leaps away, barely brushing their fingertips.