So Bad It’s Good: Finding Beauty in Imperfect Art

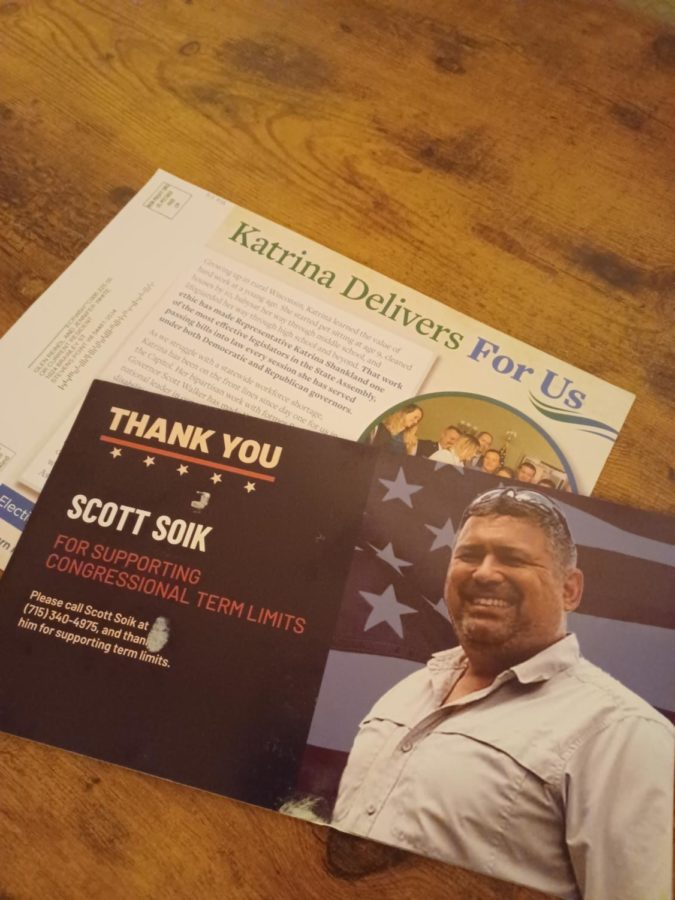

The Fred Smith Concrete Park in Philips, Wi (image taken by author)

January 20, 2022

Okay, hear me out on this one, you should consume more “bad” media.

The internet has made discourse around art really frustrating. Everything is either perfect or awful and critiques of a piece of art are often taken as personal attacks on those that like it. Nuance is dead and we killed it. I’m here to argue for another approach. An approach that’s been around for a long time and may change your relationship with art in general: an appreciation for art despite or even because of its flaws. Today we’ll be looking at two notable bad art appreciation subcultures, starting with Camp and making our way to Art Brut.

What is Camp?

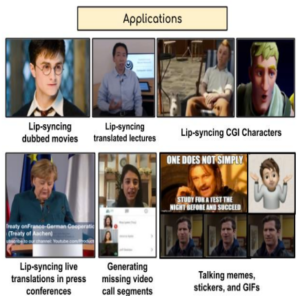

The term “Camp” was originally coined by writer Susan Sontag in her essay Notes on Camp. Though the subculture existed informally long before it had a name, especially in queer spaces, Sontag’s writing acted as a manifesto for the movement and gave it greater exposure. Sontag describes Camp art as “the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naive” and Camp taste as “a kind of love, love for human nature.” Camp is enjoying your favorite bad movie with your friends, Camp is that tacky lamp that you can’t help but sincerely love, Camp is a lens through which we can appreciate parts of the world that otherwise get passed over. Connoisseurs of Camp are steeped in a deep affection for ambitious and wildly creative works of art regardless of accepted standards of good taste. In fact Camp culture has a sort of playful relationship with the idea of “good taste”. Often Camp aficionados aren’t naive to the boundaries of good taste but instead know them well enough to effortlessly waltz atop them in a dress made to look like the lips from The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

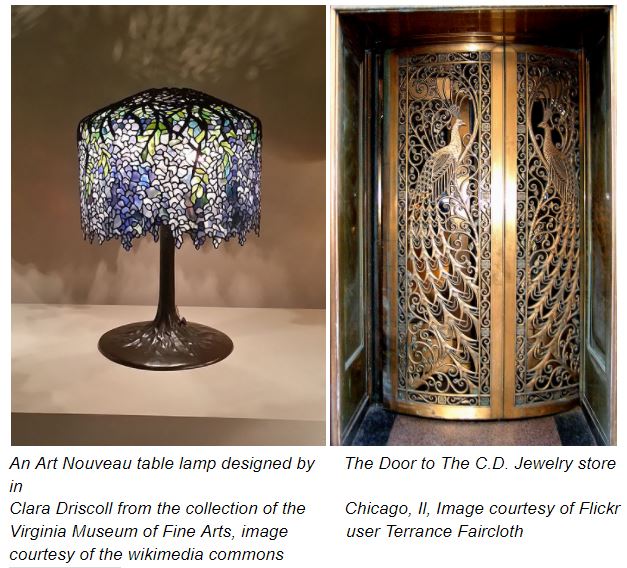

It’s equally as important to distinguish what isn’t Camp as it is to distinguish what is. A piece of art that’s just poorly executed while being completely free of any ambition or wild ideas, something that plays it safe, is distinctly not Camp and Sontag makes sure that her readers know that. To quote Sontag, “When something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition. The artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish”. On the same token, “Camp” is not a synonym for “bad”, art can simultaneously be enjoyed from serious and Camp perspectives alike. The Art Nouveau movement is one of the strongest examples of this; Art Nouveau pieces find homes in some of the greatest art collections in the world in all of their artificial and excessive glory, being enjoyed from serious artistic perspectives and disbelieving Camp perspectives all at once.

Camp Today

Once Camp had been let into the world it flourished wildly, becoming even more of a staple in the communities that had already loved it before it had a name. Examples of Camp in modern queer communities are easy to find everywhere but especially in the drag subcommunity. And of course I’d be remiss not to mention the number of independent theatres and movie viewing clubs that hold “bad movie nights”, honoring the spirit of Camp whether they’re aware of it or not. You can see an allusion to the earnest spirit of Camp in a New Statesman interview with the president of a large bad film club in England.

Bad films are generally one person’s vision. One person who often decides to do the opposite of what the film industry generally does, in order to share their unique vision with the world. Bad films are often someone’s dream that, despite their earnestness, failed to translate to screen in the way they hoped.

Of course, a natural response to Camp culture is to simply see bad works as bad, and that’s reasonable. But Camp allows us to enjoy the things around us in a different light, and to find joy in unlikely things. Rejecting Camp is rejecting that opportunity. I wanted to interview a fellow Camp lover about her relationship with all things Camp, so may I present to you, PODS student Noah Venzke.

To Noah, Camp is “taking something poorly executed that was done in good intention and bringing back the good intentions as the person consuming the media.” “Camp is really pure and innocent, I think it comes from a place of not wanting to be seen as anything not grand” When I asked her why she liked Camp, she pointed to a side of Camp that I hadn’t touched on much in this article: its countercultural nature. “I think Camp is sort of unabashedly countercultural and that’s why I like it so much … it’s just sort of saying I don’t care if you find what I’m doing cringey or trivial. Doing things whether you see it as in bad taste or not, it’s fun”

Raw Art

Camp isn’t the only subculture to appreciate rough and ambitious works of art, the Art Brut (“raw art” in french) movement appreciates art that would traditionally be cast aside as well, but from an altogether different perspective.

The term Art Brut was initially coined by formally trained artist Jean Debuffet to describe the works of patients at mental facilities that hadn’t been exposed to the art world outside. The term quickly broadened to encompass art made by professional artists trying to replicate a detached, contextless style (though many argue that it isn’t true Art Brut). The Museum of Modern Art describes Debuffet’s work as being marked by “a rebellious attitude toward prevailing notions of high culture, beauty, and good taste”.

Art Brut spread gradually through France and the rest of Europe until it ended up at the doorstep of the anglophone world in 1972 when English writer Roger Cardinal coined the term “Outsider Art”. Initially conceived as a simple counterpart for Art Brut, Outsider Art started to take on its own form a decade later in the eighties. What had once been known as “folk art” or “self taught art” started to get rolled into the broader Outsider Art category.

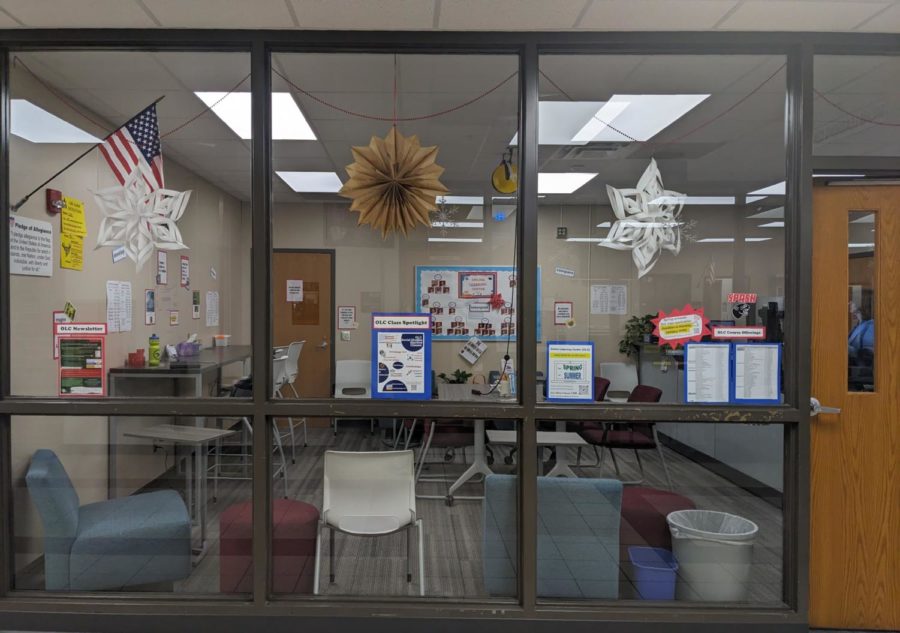

You can see a great example of Outsider Art in our own state at the Fred Smith Concrete Park near Philips, Wi. The park houses over 200 life-sized concrete and glass sculptures of human and animal figures posed around a small, cluttered roadside park. The eclectic sculptures were constructed by retired lumberjack Fred Smith over the course of 15 years.

Art Brut and Outsider Art diverged enough to become entirely different art movements with different mission statements. Outsider Art appreciated many of the same qualities as a certain segment of Camp; many things that could be considered Camp could just as easily be described as Outsider Art. Looking at a modern description of Outsider Art by New York gallerist Andrew Edlin who describes it as “made by untrained artists, that’s not academic or influenced by art-historical references.” We can see that its definition has broadened greatly in the decades since its inception.

Fear of The Outsider

Of course not everyone was a fan of this move towards a broader classification, many are upset by how broad Outsider Art has become, claiming that the term has no meaning at all anymore. Others still see a work outside of the established scene as inherently lesser. In an interview with Artsy.net, Edlin even mentioned that a lot of gallerists are trying to avoid the label, that they see it as invalidating the work.

This fear of art outside of the mainstream is easy to understand. Works can challenge our notions of what makes art good and upset the balance of our art world. This can be intimidating and I understand that, I also understand being afraid to embrace the amateurism in your own work. It can be humbling to recognize how little you know about the medium you’re working in. But I’d argue that it’s important to embrace outsiders and the amateurism in our own work. To be proud of the same raw, uninfluenced creativity that fascinated establishment artists at the birth of Art Brut and makes lovers of Camp grin. To quote Noah’s parting words to the skeptics, “I don’t know who you are, but you’re missing out. You don’t have to enjoy Camp but it’s fun, why not.” So please, don’t turn up your nose to amateur works, they might just be revolutionary.